PREVAIL: Understanding the Windows eBPF Verifier

In 2021, Microsoft open sourced their eBPF-for-Windows project. They rely on existing open-source projects to JIT-compile, interpret, and verify BPF programs. Interestingly, PREVAIL, the BPF verifier they use, originated from peer-reviewed academic work and contrasts significantly with the Linux verifier.

In this blog post, I’ll summarize the PREVAIL paper with a strong focus on its design. I will also introduce its formalism and have a quick look at the evaluations. The PREVAIL implementation evolved a lot since the paper was published in 2019, yet the design stayed the same. Some of the limitations may have been removed and the evaluation numbers may have changed.

- Introduction

- Abstract Interpretation

- Abstract Domain Requirements for PREVAIL

- Formalism of PREVAIL

- Implementation of PREVAIL and Limitations

- Accuracy and Cost Evaluations

- Conclusion

- Addendum: False Positive Example

Introduction

In this paper, the authors introduce PREVAIL1, an alternative static analyzer for eBPF bytecode, using abstract interpretation techniques. As is the usage, they introduce their results in the abstract:

Our evaluation, based on real-world eBPF programs, shows that [PREVAIL] generates no more false alarms than the existing Linux verifier, while it supports a wider class of programs (including programs with loops) and has better asymptotic complexity.

Early in the paper, the authors make one important observation:

The need for a better verifier is widely recognized by eBPF developers.

That’s true and I’m glad to see it is also clear to the academic community. They describe four aspects on which the verifier could be improved:

- First, the verifier reports many false positives, forcing developers to heavily massage their code for the verifier to accept it, e.g., by inserting redundant checks and redundant accesses.

- Second, the verifier does not scale to programs with a large number of paths.

- Third, it does not currently support programs with loops.

- Finally, the verifier lacks a formal foundation.

The first and second points are probably the main issues today. Because the verifier runs on low-level bytecode, it doesn’t have all of the high-level information from the original C program2. As a result, it sometimes struggles to keep track of and verify code optimized by the compiler3.

The second point only affects large BPF projects such as Cilium, but can be hard to resolve, as small changes in the code and compiler options can lead the verifier to reject programs. On newer kernels, support for function-by-function verification makes this a lot more manageable, by allowing developers to break programs into smaller pieces.

Support for bounded loops was merged in Linux v5.3.

It was then extended to support various loop structures of arbitrary sizes via BPF helpers (bpf_loop) and kfuncs (e.g., bpf_iter_num_next and bpf_for macro).

Finally, I’m not sure the lack of formal foundations should be an argument in itself, but I guess the point is that formal foundations would allow us to reason about the correctness of the verifier.

Abstract Interpretation

This section aims to provide a short introduction to abstract interpretation, the static analysis technique used by PREVAIL. I’ll focus on the minimal information needed to understand the paper. For a more thorough introduction, you can refer to the Mozilla wiki.

Introductory Example

Abstract interpretation is a technique for static program analysis, used to analyze a program’s behavior over all possible inputs. Since finding all possible runtime errors in an arbitrary program is undecidable, static analysis trades complete coverage of possible inputs for an approximate result (e.g., rejecting safe programs).

Abstract interpretation achieves this by using abstract values for variables. As an example, we will analyze the snippet of BPF bytecode below with integer intervals as abstract values for our variables.

This snippet of bytecode reads 16 bits from memory (instruction 4), at offset r0 + r1, with r0 pointing to a BPF map value.

At instruction 1, we check that the value in r1 is bounded. If it is not, we bound it with a bitmask at instruction 2.

// r0 is a non-null pointer to a map value.

// r1 initially can be any positive value on 64-bits.

0: r6 = r0

1: if r1 < 14 goto pc+1 // Jump to insn 3 if r1 is bounded.

2: r1 &= 0xf // If it is not, bound it.

3: r6 += r1

4: r7 = *(u16 *)(r6 + 0) // Read map value.We are interested in the value of r1 at the entry of instruction 3, before it’s used for a memory access.

The initial abstract value for r1 is [0; MAX_UINT64].

It represents the set of possible concrete values r1 can take at instruction 0.

When we reach the conditional jump, we analyze both paths.

If the condition is true, then we can update the abstract value to [0; 13].

If false, we reach instruction 2 and can update r1 to [0; 15].

So far it looks very similar to what the Linux verifier would do.

That changes at instruction 3.

Instead of continuing to analyze the two paths independently, we will use the join operation4, ⨆.

In particular, we can define the abstract value of r1 at instruction 3 as the join of r1’s abstract values after instructions 1 and 2, that is [0; 13] ⨆ [0; 15] = [0; 15].

This analysis tells us that the memory access at instruction 4 is unsafe (out of bounds) if the map value is 16-bytes long or less (2 bytes access at maximum offset 15).

See the addendum for a second example in which the integer intervals leads to a loss of precision and a false positive.

Abstract Domains

The Interval abstract domain, which we’ve used above, is only one domain among many that can be used for abstract interpretation.

We can cite for example, the Parity domain, to track odd and even numbers, or the Polyhedra domain, which can track linear relationships between variables.

The table below5 gives a few examples of abstract numerical domains, from least expressive to most expressive (c and a being constants, x variables).

The abstract domain to use depends on the application and is often a tradeoff between the computational cost and what can be analyzed.

| Numerical domain | Representable constraints |

|---|---|

| Parity | x % 2 == c |

| Interval | ±xi <= c |

| Zone | (±xi <= c) and (xi - xj <= c) |

| Octagon | (±xi <= c) and (±xi ± xj <= c) |

| Polyhedra | a1x1 + a2x2 + ... +anxn <= c, ai ∈ Z |

So for example, with the Interval domain, you could imagine having constraints x1 <= 2, -x1 <= 0, and x2 <= 0.

In other words, x1 ∈ [0; 2] and x2 ∈ ]-∞; 0].

More expressive abstract domains are also usually more expensive.

For example, while the join operation for the Interval domain has complexity O(n) (with n the number of variables), the same operation has complexity O(n²) in the Octagon domain.

One important aspect of the domain’s expressiveness is whether they are relational, meaning that they can express relations between variables.

Zone for example can preserve some relations between variables xi and xj with its second constraint type.

In the table above, we can see that Zone, Octagon, and Polyhedra are relational domains, while Parity and Interval are non-relational.

For more information on abstract domains, you can check these PLDI 2015 slides, which include a walkthrough of a program analysis with Octagon (slides 14–30). The POPL 2017 presentation from the same author includes an example assertion that can be proven by Polyhedra but not by Octagon.

Let’s go back to our PREVAIL paper.

Abstract Domain Requirements for PREVAIL

Using a couple of example BPF programs, the authors make several observations that will drive the design of PREVAIL.

An eBPF program can access a fixed set of memory regions, known at compile time. […] The program can acquire access to additional regions via the maps API [5]. Such regions can be shared by multiple processes, as well as between kernel and user-space applications.

This is a key observation for memory accesses. BPF programs can access different memory regions including the stack, context (e.g., skb_buff), packet data, and map values. All of these regions except the packet have a static size, known at the time of verification.

Because the size of the packet is not known during verification, developers of BPF programs must implement bounds checks on the packet. For example:

if (packet_ptr + access_size > ctx->data_end) return TC_ACT_DROP;This leads the authors to make the following observation:

Observation 1. The analysis must track binary relations among registers.

In other words, to understand the bounds of packet_ptr, the analysis must be able to track relations between variables (in our case, between data_end and packet_ptr + access_size).

That in turns limits the choice of abstract domain to relational abstract domains.

Observation 2. The analysis must track values in memory, including relations between different locations, as if they were registers.

This second observation comes from the use of register spilling. When all registers are in use, the compiler can move some of their contents to the stack, to load it back into registers at a later time. If we don’t track those register contents while on the stack, we would lose all of their information.

Observation 3. As eBPF programs are getting larger and more complex, verification via path enumeration is becoming infeasible.

The number of paths through a program grows exponentially with the number of branches. To scale to large programs, the Linux verifier makes use of state pruning, which allows it to recognize already-verified states. Abstract interpretation is an interesting alternative as it was designed specifically to address this problem.

Formalism of PREVAIL

I’ll now dive into the formalism of PREVAIL. I will give pointers to understand the notations and some of their underlying intuitions. If that aspect doesn’t interest you, you can skip ahead to the implementation.

Formal Representation

eBPF programs manipulate two kinds of regions: private regions, which can be accessed only by the program, and shared regions, which are used for intra-kernel inter-process communication.

The authors distinguish between private (stack, context, packet) and shared (e.g., map values) memory regions. Map values are shared memory regions because they may be modified at any time by another process or BPF program. As such, they need special handling in the verifier.

We distinguish numerical values from pointers using tags: a value tagged

numis a numerical value, while a value taggedRis a pointer offset into regionR.

PREVAIL models every variable with a tag and value.

Scalars are tagged num, stack pointers stk, packet pointers pkt, etc.

For pointers, the value represents the offset into the memory region represented by the tag.

Therefore, (pkt, 4) is a pointer at offset 4 into the packet, whereas (num, 4) represents the integer 4.

To represent the tags of shared memory regions (e.g., maps), the authors use the sizes of these regions:

First we abstract the tags of pointers to shared regions by the sizes of the regions they point to. This bounds the number of possible tags in any program P.

The downside of this simple approach is that PREVAIL can’t tell two pointers to shared regions of the same size apart. The authors therefore need to forbid subtractions and comparisons between such pointers.

as we can no longer tell whether two pointers to a shared region of size K point to the same region or not, we strengthen Safe() to forbid subtraction and less-than comparison between such pointers.

Because of that change, PREVAIL can reject BPF program the Linux verifier would accept, but I doubt many programs are in this case in practice.

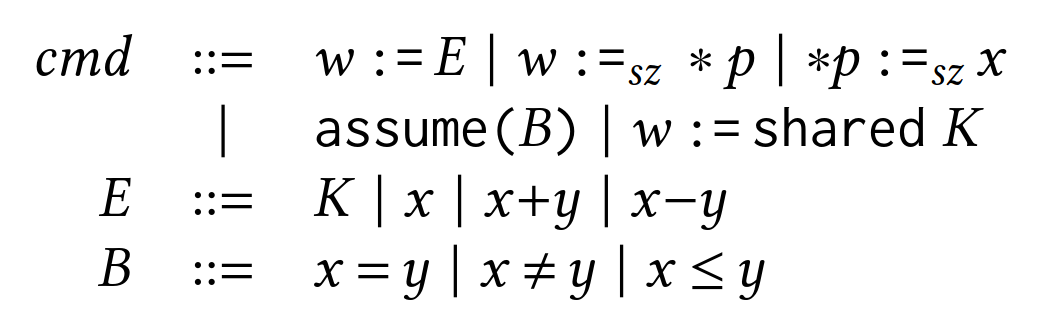

The grammar in the above figure formalizes the primitive eBPF operations that PREVAIL supports.

The first operation defines assignments and ALU operations, while the second and third define load and store instructions respectively.

assume is used to state the conditions of conditional jumps.

shared K returns a pointer to a shared memory region of size K, typically for a BPF map lookup.

Formalizing Memory Writes

In the following, I will focus on the formalism for the store operation, used to write to memory. See the paper for other operations.

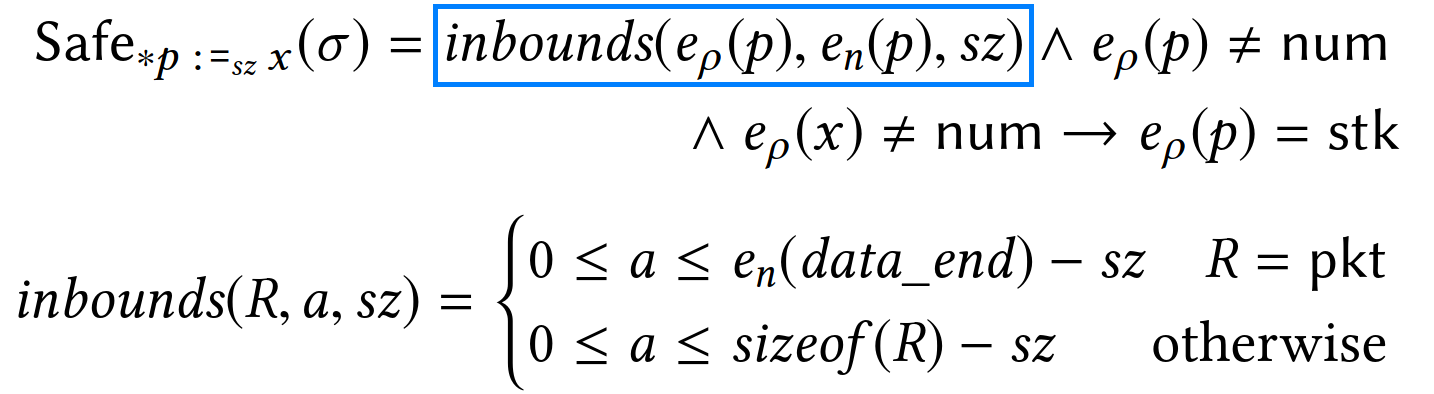

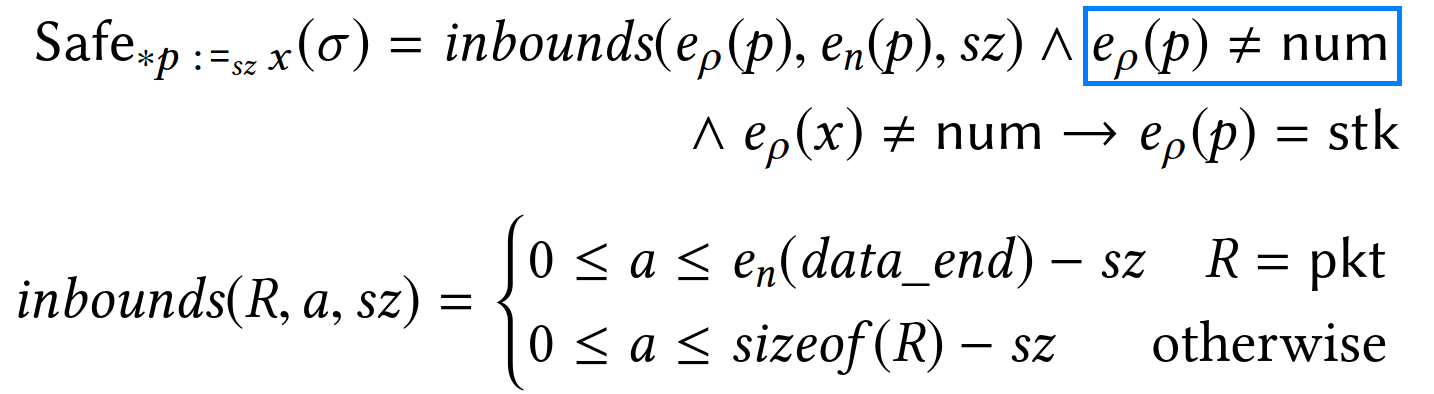

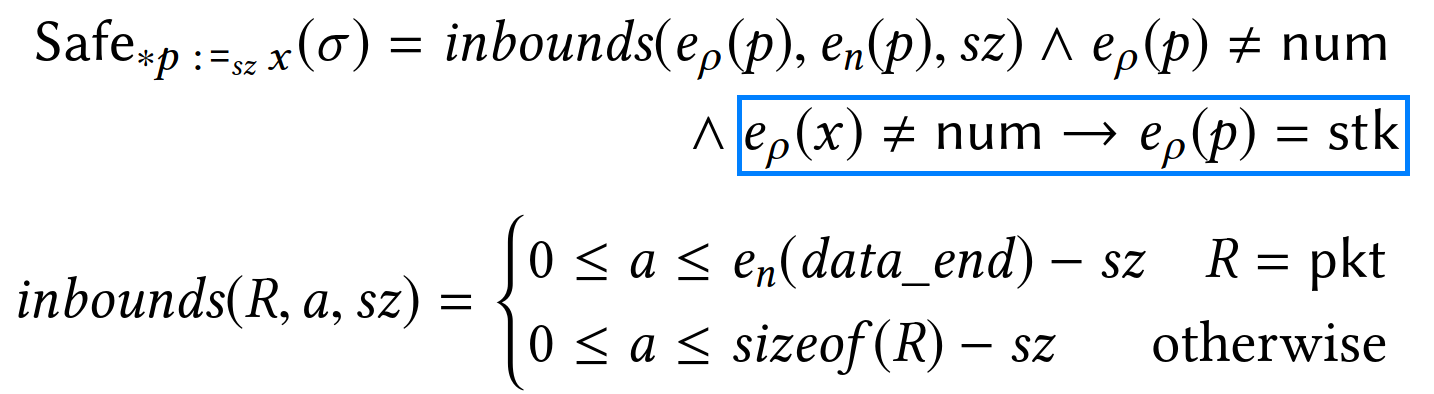

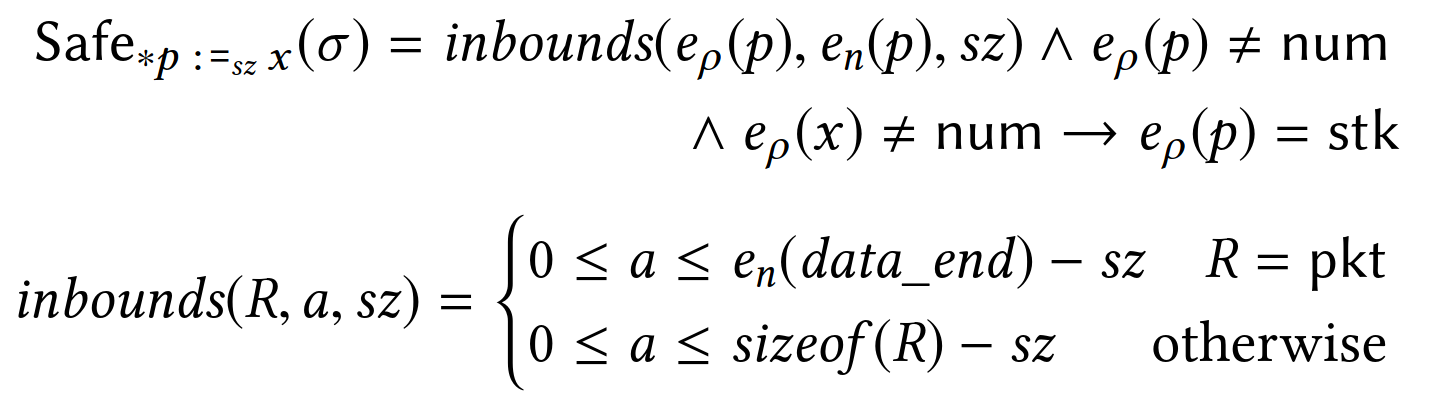

PREVAIL deems a store of sz bytes at memory pointed by p safe if:

- it is within the bounds of the memory region of

p, notedeρ(p), and pis a pointer (i.e., not taggednum), and- in case the stored value

xis a pointer,ppoints to the stack.

The third condition is meant to ensure that pointers are never written to externally-visible memory locations (e.g., the packet) as that would lead to pointer leaks.

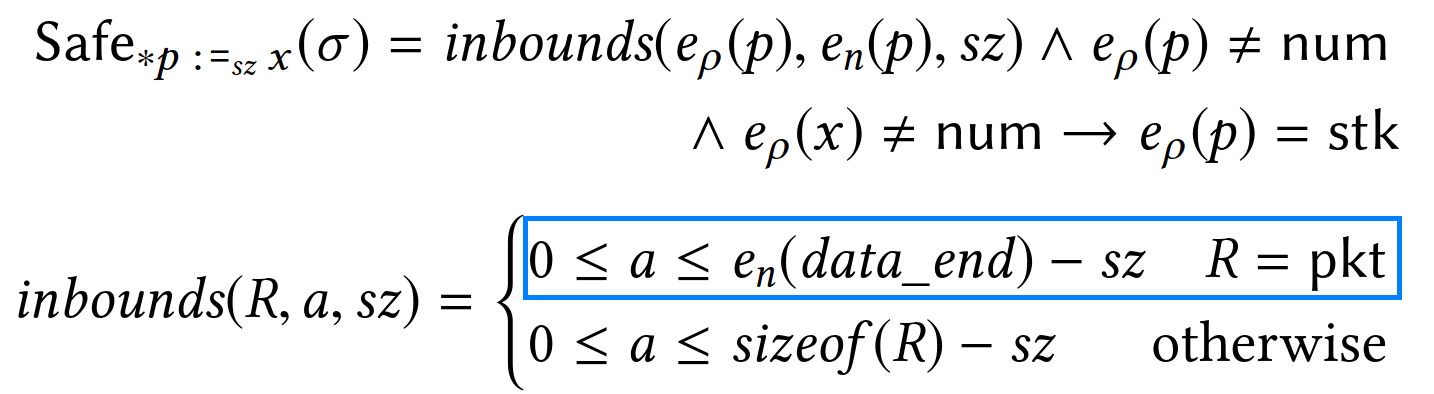

You can also notice that in case p is a packet pointer, the upper-bound check is performed against the special variable data_end instead of the static region size, sizeof(R).

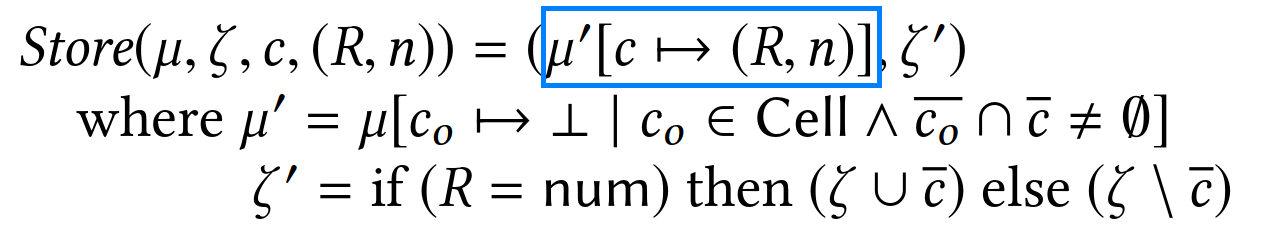

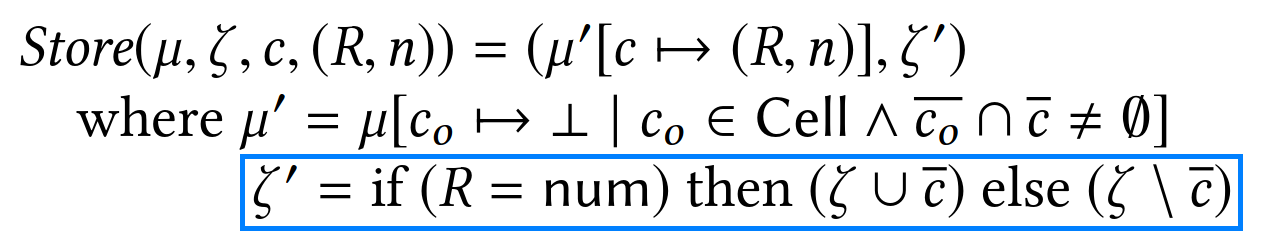

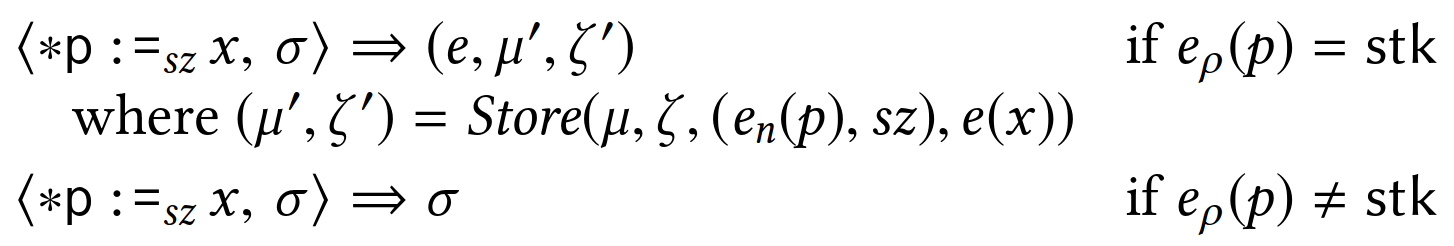

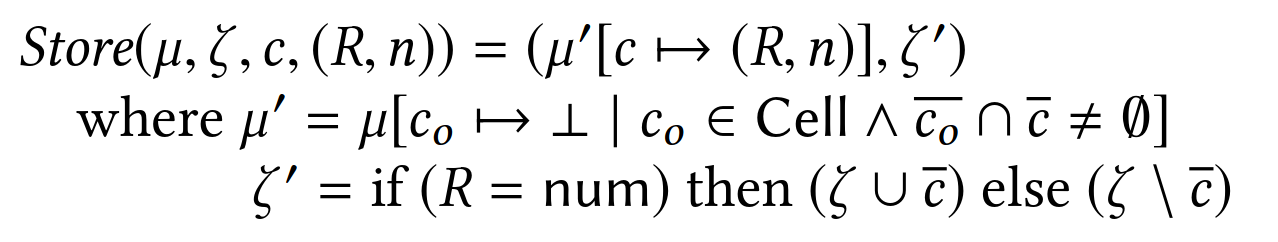

The authors then define how the different eBPF operations impact the verification state.

The verification state is defined by the triple σ = (e, μ, ζ), with e being the set of registers, μ the set of memory cells on the stack, and ζ the set of stack addresses holding scalars.

The example for an assignment of immediate value K to register w is trivial; it simply associates register w to state (num, K) in e:

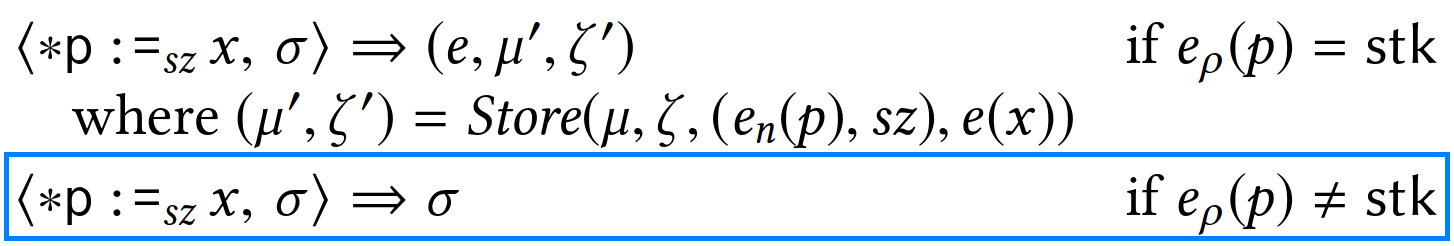

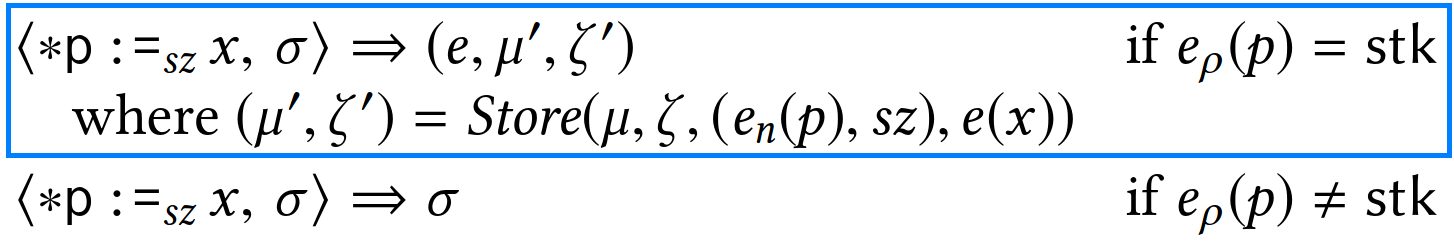

As shown below, the store operation is a bit more involved to track.

First, if the store is to a region other than the stack, the verification state can be left as is; it doesn’t need to be tracked.

Otherwise, both μ and ζ need to be updated.

In μ, the register e(x)=(R,n) is associated to the memory cell defined by its position en(p) and size sz.

Any other memory cell overlapping with this store is removed from μ.

Finally, addresses overwritten by the store are added or removed from ζ depending on whether the stored register x holds a scalar or not.

Implementation of PREVAIL and Limitations

The implementation section helps to understand the main limitations of PREVAIL. Most of those limitations are simply gaps in the initial implementation and are not caused by the use of abstract interpretation.

[PREVAIL] maintains a variable for every one of (the finite number of) possible cells in the memory, and instantiates the underlying domains to track the values as if every cell is a (syntactic) analysis variable

Each stack slot (memory cells μ, if you’ve read the formalism section) is tracked as a separate variable.

As we’ve seen in the introduction to abstract domains, the complexity of abstract domain operations usually grows with the number of variables.

So PREVAIL is likely to consume significantly more resources for BPF programs using a lot of stack slots.

PREVAIL translates eBPF binaries into a CFG-based language understood by Crab [30]—a parametric framework for modular construction of abstract interpreters.

Note this intermediate Crab language was later removed (cf. vbpf/ebpf-verifier#87). That led to a significant reduction of the memory consumption.

We encode abstract tags as constant numbers and used the same abstract domain to track values and tags together. […] We handle null checks by tracking absolute values of pointers in addition to offsets

I was a bit surprised by these changes. I would have thought tags could be encoded with a much simpler abstract domain than values. But I also thought the null checks could have been handled with additional tags as in the Linux verifier6 to avoid having to track absolute values of pointers.

Bitwise operations are not tracked precisely. Instead we use efficient over-approximations, e.g., we approximate

w &= x(bitwise and) whenx > 0withassume(w<x).

PREVAIL over-approximates bitwise operations, potentially leading to false positives.

The Linux kernel does the same, but with what looks like a much more precise over-approximation, using tristate numbers (tnums).

The initial PREVAIL implementation also doesn’t support a lot of the more advanced eBPF features, such as BPF function calls, packet resizing, map-in-maps, and most helpers. This lack of support would clearly prevent the use of PREVAIL for the largest BPF users out there (e.g., Cilium and Katran), but there do not seem to be any real blockers to their implementation.

Support for 32-bit arithmetic was also missing, which means programs compiled with mcpu=v3 would likely be rejected7.

That was covered last year (cf. vbpf/ebpf-verifier#419).

Our verifier does not currently implement termination check.

Finally, at the time the paper was written, PREVAIL didn’t ensure programs terminate.

That was fixed in 2021 (cf. vbpf/ebpf-verifier#139) with a new abstract value max_instructions.

The constraint max_instructions < 100000 is added such that the longest path through the program can have at most 100k instructions8.

Accuracy and Cost Evaluations

The authors evaluate the accuracy (number of false positives) and runtime cost (duration and memory consumption of the analysis) of PREVAIL. To that end, they rely on a corpus of 192 BPF programs from six open source projects including Linux, Open vSwitch, Suricata, and Cilium. BPF programs in the corpus are either of a small size (e.g., Linux samples) or networking-related; it doesn’t include any large tracing program for example. The Cilium samples are also quite old and appear to have been generated with options that don’t maximize the programs’ size and complexity. Nevertheless, the corpus includes a good variety of programs, with some in the thousands of instructions.

The authors first measure the accuracy of PREVAIL when using different abstract domains. The Interval domain is clearly not adapted to verify BPF programs and serves more as a reference. This evaluation is useful to guide a choice between the other, more expressive domains. Since, as we will see, the accuracy also depends on the implementation of those domains, the choice is not apriori obvious.

the numerical abstract domains used in our final evaluation are:

I mentioned all of these domains before and, here again, they are ordered from least expressive to most expressive. Elina and Crab refer to the libraries used to implement those abstract domains. Online decomposition is an optimization that partitions the set of program variables into disjoint subsets maintained throughout the analysis. Since the cost of most abstract domain operations grows exponentially with the number of variables, this optimization helps limit that growth.

| Abstract domain | Number of programs for which verification failed |

|---|---|

| interval | 64/192 |

| zone-crab | 2/192 |

| zone-elina | 2/192 |

| oct-elina | 2/192 |

| poly-elina | 23/192 |

The above table shows the number of programs that each abstract domain was unable to verify among the corpus. As expected, Interval was only able to verify two thirds of all programs, probably because it can’t track relations between variables. Conversely, the result for poly-elina is surprisingly bad given Polyhedra is the most expressive domain in the set. The authors however explains that this is due only to a limitation of the Elina implementation of that domain:

The implementation uses 64-bit integers for representing the coefficients, and falls back to top when the coefficients cannot be represented precisely using 64 bit.

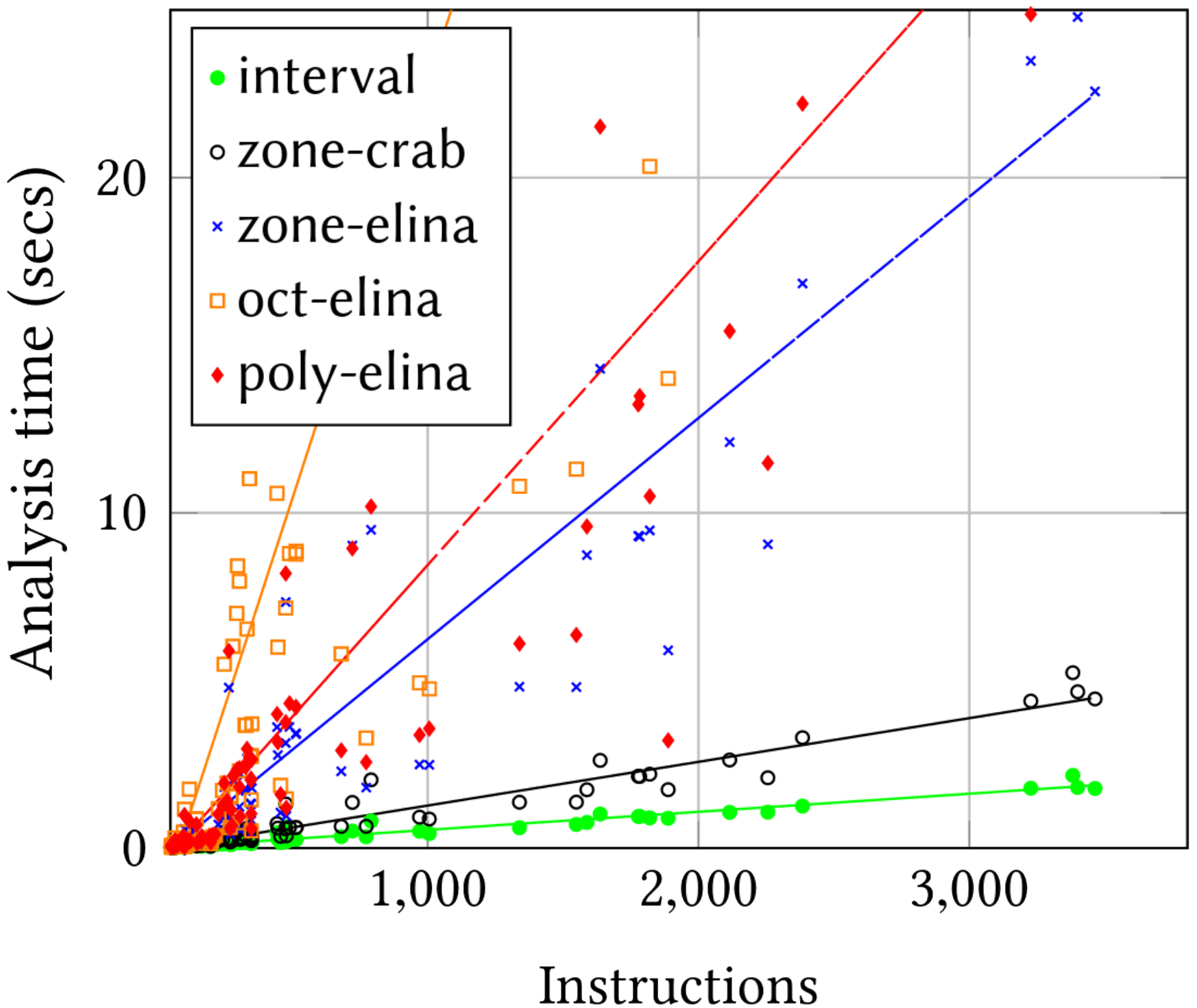

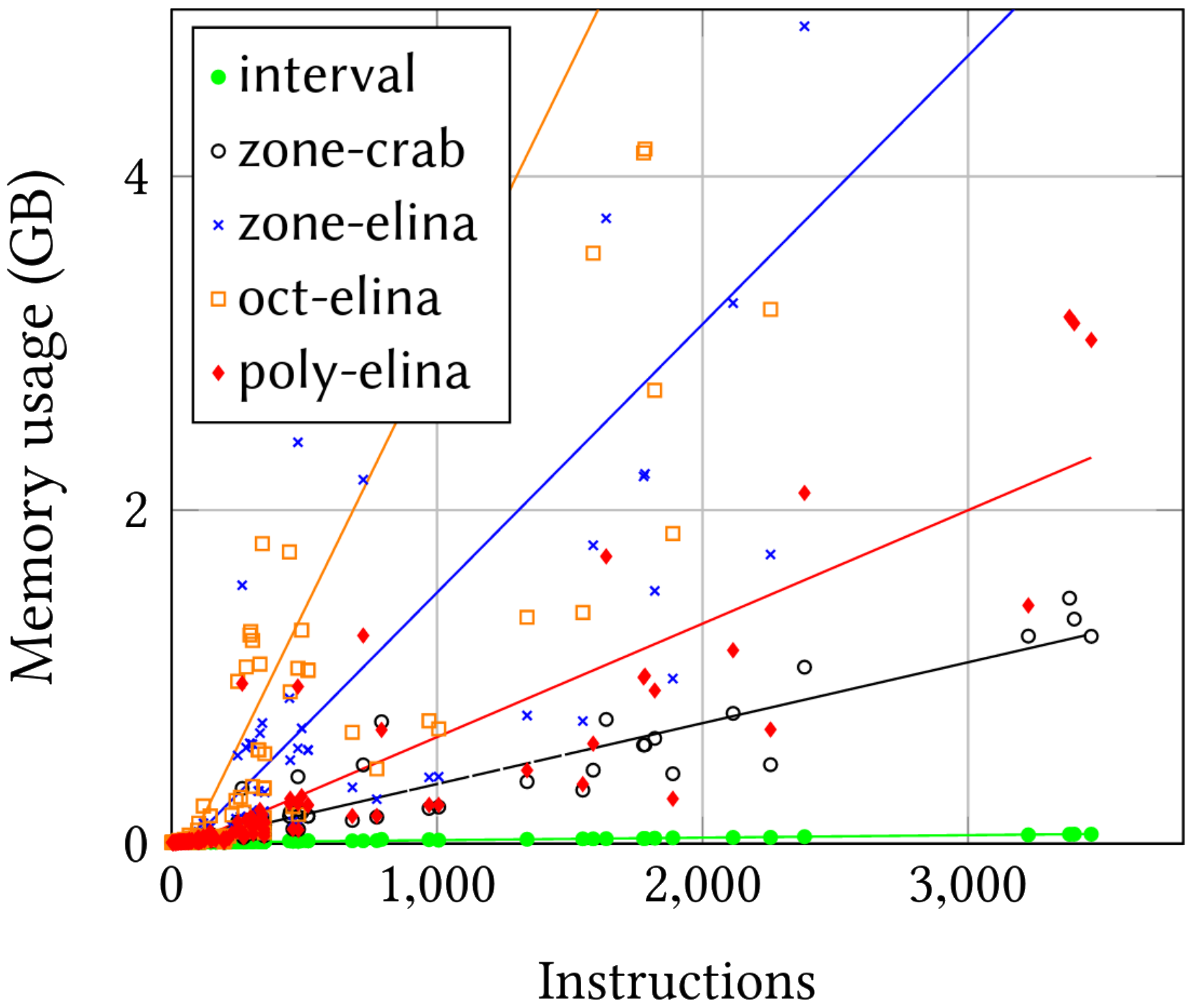

Of course, more expressive abstract domains come at a price. The following two figures represent the verification time in seconds (left) and the memory consumption in GB (right) for each abstract domain.

The Interval domain has the lowest costs. All other domains have much larger costs, except maybe for zone-crab which still requires around 5s and 1.5GB of memory to verify the largest programs. Given that 1.5GB of memory is still too much for the Linux kernel, the authors suggest running PREVAIL in userspace9.

As a point of comparison, the Linux kernel takes about a second and consumes only MBs of memory in the worst case. That makes it faster than even the Interval domain. Of course, as the authors note, the current corpus is biased toward the Linux verifier since all its programs were successfully loaded on Linux.

The actual runtime of zone-crab is roughly linear in the number of instructions, despite its cubic worst-case asymptotic complexity.

As the authors note, if zone-crab behaves well in practice, it’s worst-case runtime is actually cubic.

It would be interesting to see if it’s possible to craft a BPF program that exhausts the verifier’s resources in this way.

The Linux verifier faces the same threat and currently mitigates it by enforcing various complexity limits on the input programs (e.g., BPF_COMPLEXITY_LIMIT_STATES).

It’s a bit disappointing that the paper doesn’t include any comparison with the Linux verifier on the same corpus of BPF programs. The authors also mention PREVAIL was able to verify nine programs rejected by the Linux verifier, but without providing more details.

Conclusion

I’m always super excited to read about alternatives to the Linux BPF verifier, and this paper is no exception! If like me you don’t have a background in formal methods, the paper can be a bit hard to understand. Hopefully, I gave enough pointers in this blog post to help with that. Definitely worth a read!

This academic project is also one of the lucky few that already had a “real-life” application two years after their publication. The implementation evolved a lot during those two years and continues to. It would therefore be interesting to see how the performance compares to two years ago—and maybe how it now compares to the Linux verifier.

Thanks to Aditi for her review and suggestions on an earlier version of this post!

Addendum: False Positive Example

Using integer intervals to track the possible values of variables can be imprecise, even if your variables are indeed integers.

Consider the example bytecode below.

We bound check r1 and r2, then multiply them together, and use the result to decide whether to execute a division by zero.

We want to check with abstract interpretation if the division by zero will ever be executed.

0: r0 = 0

1: if r1 > 10 goto pc+4 // r1 ∈ [0; 10]

2: if r2 > 10 goto pc+3 // r2 ∈ [0; 10]

3: r1 *= r2 // r1 ∈ [0; 100]

4: if r1 != 11 goto pc+1

5: r1 /= r0 // Division by zero!

6: exitAfter instruction 2, both r1 and r2 have abstract value [0; 10].

After instruction 3, r1 holds the multiplication of r1 and r2 and therefore has abstract value [0; 100].

When considering the condition at instruction 4, because 11 ∈ [0; 100], we will walk both paths and hit the division by zero.

Except we know that r1 can never take value 11.

There are no two numbers between 0 and 10, that once multiplied together, can give 11 (said otherwise, 11 is a prime number).

When using integer intervals as abstract values, we will lose that information during the multiplication.

That loss of precision can lead to false positives, such as rejecting a program because of a never-executed division by zero in our example.

↩

Footnotes

-

PREVAIL stands for “Polynomial-Runtime eBPF Verifier using an Abstract Interpretation Layer”. ↩

-

That is quickly changing with BTF, which can preserve type information from the C program. ↩

-

For example, Clang 11.0.0 sometimes moves NULL checks after pointer arithmetic on map values, which causes the verifier to error with “

pointer arithmetic on map_value_or_null prohibited, null-check it first”. ↩ -

Abstract interpretation defines other operations on abstract values, such as widening and narrowing, which can be used to analyze loops without walking each iteration. ↩

-

Taken from the POPL 2018 presentation by Gagandeep Singh. ↩

-

See my introduction to eBPF instruction sets for details. ↩

-

There don’t seem to be any blockers to increase this limit and Dave Thaler suggested it could be configurable. ↩

-

That is how the eBPF-for-Windows project ended up using PREVAIL. ↩