BMC: Accelerating Memcached using Safe In-kernel Caching and Pre-stack Processing

Tomorrow, Yoann Ghigoff et al. will present their paper BMC: Accelerating Memcached using Safe In-kernel Caching and Pre-stack Processing at NSDI 2021. In this paper, the authors propose to speed up Memcached using eBPF by implementing a transparent, first-level cache at the XDP hook. It’s not everyday we see BPF being used on application protocols!

This blog post is a summary of the paper and its main results. Full disclosure, I used to work with some of the authors.

Introduction

Memcached is a popular key-value store, most often used as a cache by other applications. BMC acts as a first-level cache in front of Memcached:

We present BMC, an in-kernel cache for Memcached that serves requests before the execution of the standard network stack. […] Despite the safety constraints of eBPF, we show that it is possible to implement a complex cache service.

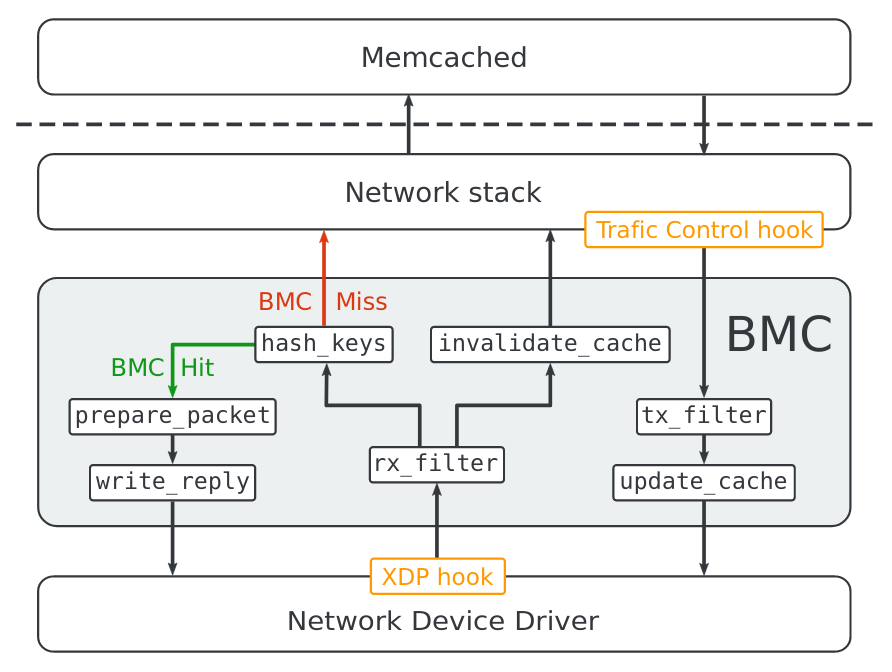

BMC relies on eBPF and intercepts packets at the XDP and tc hooks, on ingress and egress respectively. As we will see, one of the challenges of the implementation is to work around the complexity constraints of the eBPF verifier.

Because BMC runs on commodity hardware and requires modification of neither the Linux kernel nor the Memcached application, it can be widely deployed on existing systems.

That is often true of BPF-based applications. Here in particular, because BMC is a transparent cache, it doesn’t require changes to Memcached.

BMC focuses on accelerating the processing of small GET requests over UDP to achieve high throughput as previous work from Facebook [13] has shown that these requests make up a significant portion of Memcached traffic.

I like that the authors state the target traffic early in the paper. They target small UDP requests, but since BMC acts as a first-level cache, they can always fallback to Memcached for unsupported requests.

This provides the ability to serve requests with low latency and to fall back to the Memcached application when a request cannot be treated by BMC.

Of course, if your Memcached application listens only on TCP, BMC won’t be of much use.

Memcached UDP Shortcomings

The authors first look at the UDP performance of Memcached and its CPU bottlenecks. In userspace, Memcached consists of well-optimized data structures to handle key-value pairs, with an LRU algorithm to evict “stale” data.

The data management of Memcached has been well optimized and relies on slab allocation, a LRU algorithm and a hash table to allocate, remove and retrieve items stored in memory.

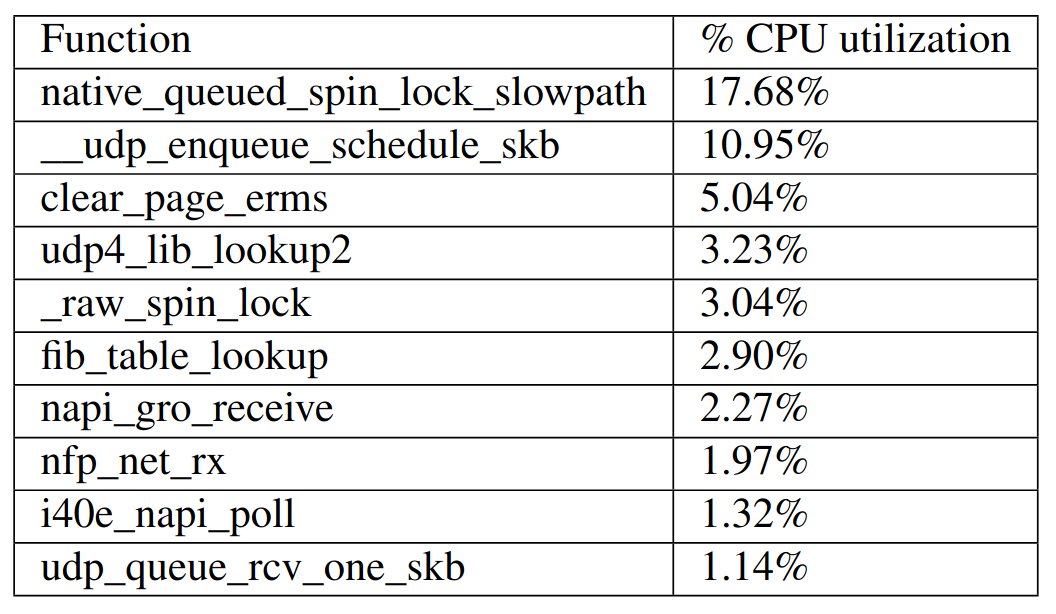

The kernel however accounts for a large portion of Memcached’s CPU consumption, mostly to send and receive data over the network. The authors evaluate that more than half of the CPU time is spent in the kernel, with an increasing portion as the number of threads increases.

The kernel functions listed above illustrate that a lot of CPU cycles are wasted on lock contention because a single UDP socket is used.

Instead of comparing BMC against this slow Memcached, the authors patch Memcached to support multiple sockets thanks to SO_REUSEPORT.

Supporting multiple sockets helps scale across cores, with a 6x performance improvement when using 8 cores.

This patched Memcached makes for a more realistic comparison to BMC, since after all, Facebook uses a similar optimization (though without SO_REUSEPORT).

It’s a bit surprising that vanilla Memcached doesn’t already include this optimization. At the time I’m writing this, the authors have not tried to submit their patch upstream (yet).

BPF’s Complexity Constraint

Since a large part of the paper discusses how the authors worked around the complexity constraints of the verifier, they provide a bit of background on BPF bytecode verification before diving into the design.

All conditional branches are analyzed to explore all possible execution paths of the program. A particular path is valid if the verifier reaches a

bpf exitinstruction and the verifier’s state contains a valid return value or if the verifier reaches a state that is equivalent to one that is known to be valid. The verifier then backtracks to an unexplored branch state and continues this process until all paths are checked.

This succinct explanation contains a lot of information, so let’s unpack it.

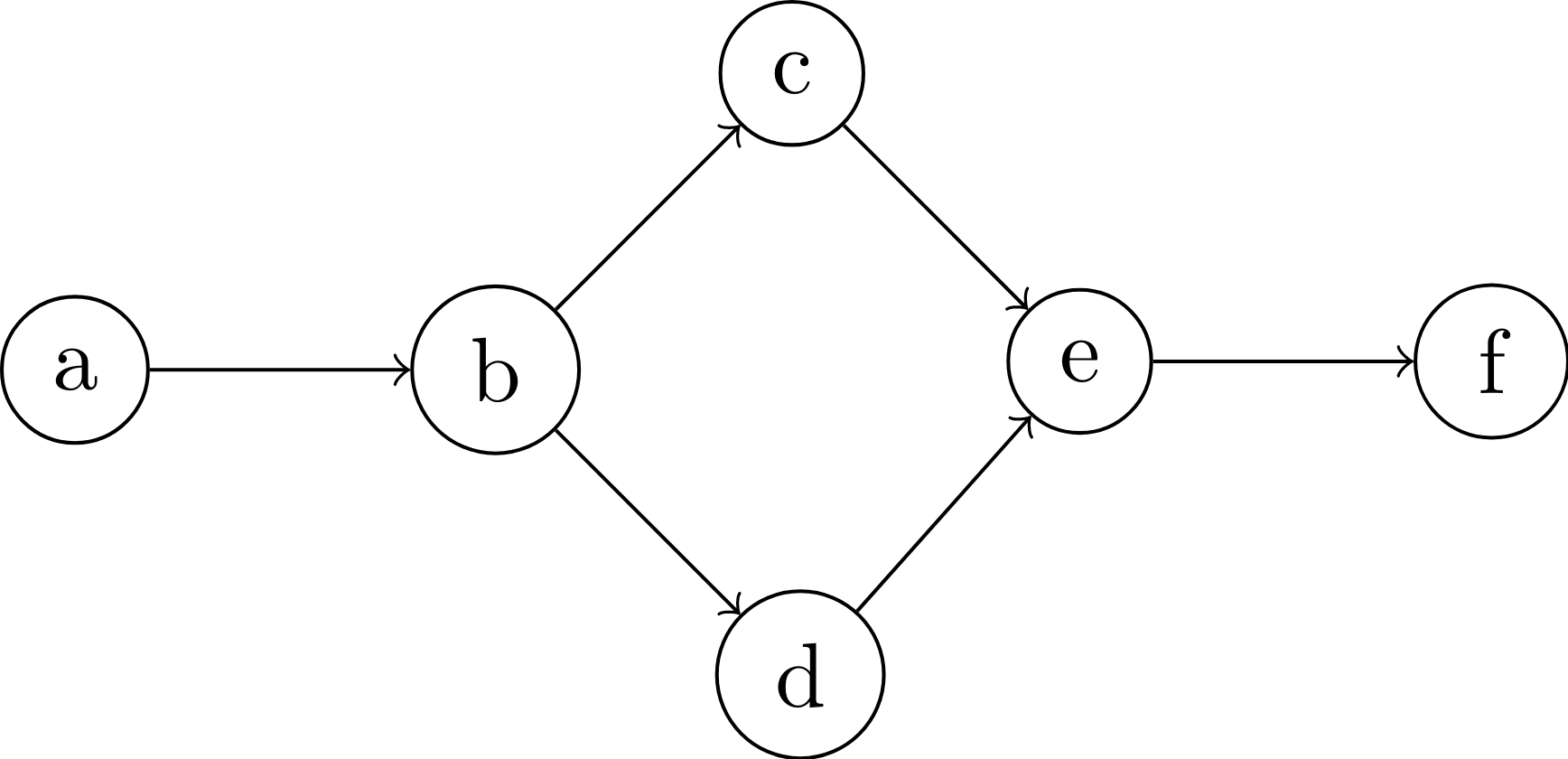

The BPF verifier must ensure all paths through the program are valid, so in the example below that means a.b.c.e.f and a.b.d.e.f should be valid.

As it walks each path, the verifier infers bounds and types for all stack slots and registers (the aforementioned verifier state).

That information is used to validate the correctness of instructions (e.g., memory loads are bounded, potential null pointers are not dereferenced) until the exit instruction is reached, at which point the path is deemed valid.

At that point, the verifier backtracks to an unexplored branch and continues, so in our example, it may analyze a.b.c.e.f then backtrack to d to analyze d.e.f for the second path.

The number of instructions to analyze increases exponentially with the number of branches so the verifier has one additional trick to scale, state pruning.

At specific instructions1, it compares the current state to previously validated states.

If the current state is equivalent to a previouly validated state, then there’s no need to walk the rest of the path.

Thus, in our example, when analyzing e for the second time, if the verifier’s state is equivalent to the state it had when it walked e the first time, it will skip the analysis of f.

Finally, the verifier maintains an instruction budget: how many instructions it will analyze before giving up. On recent kernels (v5.2+), this budget is of 1 million instructions and constitutes the main complexity constraint. I’ll refer to the number of instructions a program would need to be fully verified as the complexity of that program.

Caching Behavior

To act as a transparent cache, BMC must build its own copy of a subset of Memcached’s data.

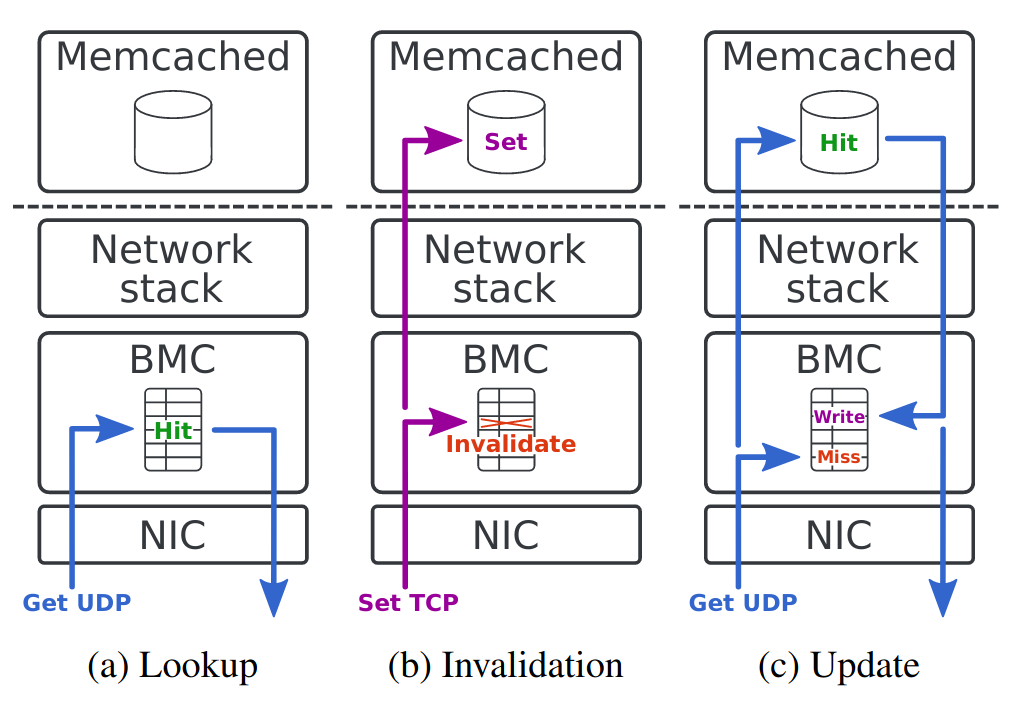

To that end, BMC intercepts all SET and GET requests as illustrated below.

It learns the new (key, value) entries by intercepting the responses to GET requests from Memcached (Update case).

For keys that were already requested once before, BMC can reply without involving Memcached in userspace (Lookup case).

Finally, when intercepting SET requests, BMC simply invalidates its corresponding (key, value) entry (Invalidation case).

Since a SET request updates the value for a key, BMC needs to ensure it won’t answer with the wrong key on the next GET request.

You may wonder why BMC doesn’t simply update its local cache when intercepting SET requests. The authors provide two reasons:

We choose not to update the in-kernel cache using the SET requests intercepted by BMC because TCP’s congestion control might reject new segments after its execution. Moreover, updating the in-kernel cache with SET requests requires that both BMC and Memcached process SET requests in the same order to keep the BMC cache consistent, which is difficult to guarantee without a overly costly synchronization mechanism.

Because of the variable-sized keys and values, the authors can’t reuse BPF’s hash table, so they have to build their own.

It is a direct-mapped cache, meaning that each bucket in the hash table can only store one entry at a time. BMC uses the 32-bit FNV-1a [21] hash function to calculate the hash value.

Their hash table is very simple and doesn’t provide any collision resolution, probably because doing so in BPF would be costly in terms of instructions. In case of hash collisions, requests can always be processed by Memcached in userspace.

This simple data structure also keeps concurrent accesses simple:

The BMC cache is shared by all cores and does not require a global locking scheme since its data structure is immutable. However, each cache entry is protected from concurrent access using a spin lock.

BPF Implementation

The BPF implementation and subsequent evaluation constitute in my opinion the crux of this work. To compute hashes and copy keys and values, BMC loops2 over the data, byte by byte. This is of course very costly in instructions and a naive implementation would rapidly eat the entire verifier instruction budget.

BMC uses a loop to copy keys and values from a network packet to its cache, and vice-versa.

To avoid spending too many instructions on each requests, the authors first restrict the requests BMC will process:

To ensure the complexity of a single eBPF program does not exceed the maximum number of instructions the verifier can analyze, we empirically set the maximum key length BMC can process to 250 bytes and the maximum value length to 1000 bytes. […] According to Facebook’s workload analysis [13], about 95% of the observed values were less than 1000 bytes.

The few requests BMC can’t process will be served by Memcached in userspace, so the only downside here is a small loss in caching efficiency.

Those restrictions are not enough to keep the BPF program under the 1 million instructions limit. The authors thus need to split it into smaller programs, joined by tail calls, as in the following figure.

Processing of Memcached requests is therefore divided into 7 BPF programs each with their own task, including computing key hashes, preparing the reply packet, or writing data into the local cache or the reply packet.

Speaking of the reply packet, you may be wondering how BMC creates it given BPF doesn’t have a helper to create and send packets. It turns out that they simply recycle the received packet, in a manner that has become common among BPF developers3:

This eBPF program increases the size of the received packet and modifies its protocol headers to prepare the response packet, swapping the source and destination Ethernet addresses, IP addresses and UDP ports.

Evaluations

The authors start the evaluation by measuring the size and complexity of their BPF programs, which I plotted below (don’t miss the second y axis for the complexity). They use LLVM 9.0 with the v1 instruction set and Linux v5.3.

We can first notice that programs which loop over the packet’s playload (update_cache, hash_keys, invalidate_cache, and write_reply) have much higher complexity.

There is also no apparent relation between the number of instructions and the complexity.

This may seem counterintuitive, but is due to the use of loops: a program with very few instructions may have a high complexity if the verifier needs to walk all iterations of the loop.

Thus, even though hash_keys has fewer instructions than prepare_packet (142 vs. 178), because it uses a loop to iterate over each byte of the keys, it has a much higher complexity (788k vs. 181).

The correlation between the number of x86 and eBPF instructions is a lot clearer. The JITed programs usually require a few more instructions than their bytecode counterparts, due in part to the x86 prologue & epilogue and the inlining of some helpers4.

The authors then dive into the throughput evaluations. They compare BMC to their patched Memcached, named MemcachedSR, and an unpatched Memcached.

They allocate 2.5 GB of memory to BMC and 10 GB to Memcached in userspace, which makes for a fairly small Memcached compared to production servers5. Their evaluation workload consists of 100 million key-value pairs, in which keys are requested following a Zipf distribution with skewness 0.99. This highly-skewed distribution is very much in favor of any caching mechanism such as BMC. Production workloads are also highly skewed (cf. Facebook’s paper, figure 5), but it’s unclear if the two are comparable. A small change is skewness seems likely to have a strong effect on the performance of BMC.

The authors first measure the throughput as the number of cores grows. This evaluation shows that:

- The patched Memcached, MemcachedSR, scales a lot better than vanilla Memcached.

- Memcached + BMC significantly outperform Memcached running alone, whether it is patched or not.

Of course, performance also depends on how many requests BMC can process given its limitations. The authors therefore evaluate the performance as the number of supported requests (with values smaller than 1KB) increases.

We can see that even with a small number of supported requests (25%), BMC already triples the performance of Memcached.

The paper has a lot more evaluations which I won’t reproduce here, including:

- An evaluation showing BMC improves performance even when using 0.1% of total memory. This is largely due to the skewed key distribution, but impressive nonetheless!

- A comparison to a DPDK-based implementation of Memcached, Seastar, which BMC outperforms while using fewer CPU resources.

Discussion on Limitations

A reason to these strong throughput results is the use of XDP, which allows BMC to answer to GET requests very early in the Linux network stack. Intercepting and processing TCP requests at this point in the stack would however be difficult, which is why BMC is currently limited to UDP requests. This also limits the relevance of BMC for other key-value stores such as Redis.

Because Redis requests are only transmitted over TCP, adapting BMC to Redis requires the support of the TCP protocol. This can be done by either sending acknowledgements from an eBPF program or reusing the existing TCP kernel implementation by intercepting packets past the TCP stack.

As pointed out by the authors, they could intercept TCP requests higher up in the Linux stack, but the performance benefit would then be smaller.

The authors note another interesting limitation, directly derived from the use of BPF:

Although static memory allocation enables the verification of BMC’s eBPF programs, it also wastes memory. BMC suffers from internal fragmentation because each cache entry is statically bounded by the maximum data size it can store and inserting data smaller than this bound wastes kernel memory.

Dynamic memory allocation would help a lot here!

Conclusion

It’s hard to say how relevant this work is to production Memcached servers. Several clues6 seem to indicate Memcached may be more common over TCP, except maybe at Facebook. It’s also unclear that CPU—and not memory—is the bottleneck on most Memcached servers.

In any case, it’s exciting to see BPF applied to application protocols. The authors managed to create a high-performance cache for an application protocol despite the constraints of the BPF verifier. And although I would have loved to see throughput evaluations for other key distributions, the paper’s evaluations are fairly extensive. They highlight various trade-offs of BMC vs. MemcachedSR. Go check it out!

The source code of BMC and MemcachedSR is on GitHub, with steps to reproduce at home.

-

How the pruning points are determined depends on kernel versions, but they may include helper calls or branch targets. ↩

-

BMC requires Linux 5.3+. ↩

-

For example, Cilium performs the same action to answer ARP queries. ↩

-

Inlining helpers (array map lookup, tail calls) requires the addition of bounds checks. ↩

-

Facebook has been reported to have 384GB of memory for their Memcached servers. ↩

-

Seastar performs a lot better over TCP and Memcached has this lock contention over UDP sockets. Could it be because users are more interested in the TCP performance? ↩