hXDP: Efficient Software Packet Processing on FPGA NICs

Tomorrow, Marco Spaziani Brunella et al. will present their paper hXDP: Efficient Software Packet Processing on FPGA NICs at OSDI 2020, or rather, the video they recorded will be played at OSDI 2020. In this paper, the authors investigate the execution of XDP BPF programs in FPGA-powered NICs.

This blog post is a summary of the paper and its results, lightly edited from my reading notes.

Introduction

In Linux, the XDP hook enables running BPF programs on the receive path of packets, in the drivers, right after the DMA. It is an easy way to run high-performance packet processing programs without the hassle of kernel bypass techniques. hXDP enables running those same programs on FPGAs.

As is the usage, the authors announce their results in the abstract:

We implement hXDP on an FPGA NIC and evaluate it running real-world unmodified eBPF programs.

“Real-world unmodified eBPF programs” sounds impressive. Programming FPGAs requires a lot of expertise and being able to do so via simpler-to-write BPF programs would certainly be a big step forward.

Our implementation is clocked at 156.25MHz, uses about 15% of the FPGA resources, and can run dynamically loaded programs. Despite these modest requirements, it achieves the packet processing throughput of a high-end CPU core and provides a 10x lower packet forwarding latency.

That throughput (same as a single high-end CPU core) isn’t particularly impressive. It sounds like the authors made the choice to use fewer resources on the FPGA at the cost of lower performance. Let’s read on to see if that is a constrained or deliberate choice :-)

Compared to other NIC-based accelerators, such as network processing ASICs [8] or many-core System-on-Chip SmartNICs [40], FPGA NICs provide the additional benefit of supporting diverse accelerators for a wider set of applications.

At a high level, you can divide widely-available programmable devices into ASIC-based devices such as Barefoot Networks’ Tofino chipset, NPU/SoC such as the Netronome SmartNICs cited above, and FPGA-based NICs as used in Microsoft’s data centers. I’m not sure I would say FPGAs can support more applications than e.g. Netronome’s SmartNICs, but they are expected to perform a lot better.

Design Goals

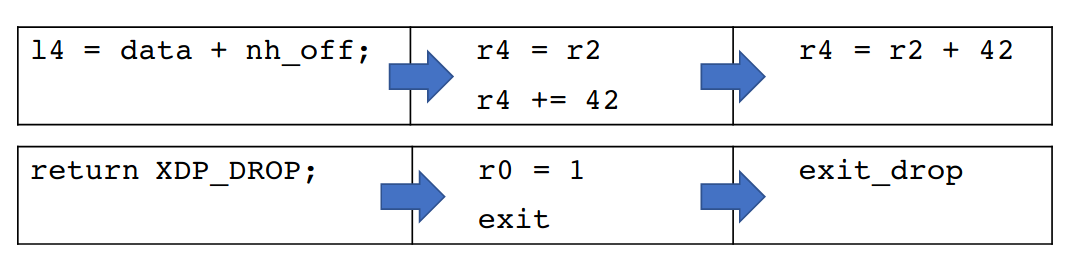

The authors then give a quick overview of how hXDP works. hXDP first performs several compile-time optimizations of the BPF program, to remove unnecessary instructions and tailor some of the other instructions to the FPGA. To that end, they defined several extensions to the eBPF bytecode:

Second, we define extensions to the eBPF ISA to introduce 3-operand instructions, new 6B load/store instructions and a new parametrized program exit instruction.

As a result, although it’s probably possible to use the same C BPF program, a different bytecode and a new compiler are needed.

Second, hXDP performs a static analysis of the BPF program to be able to parallelize the execution of independent instructions on the FPGA. FPGAs have low frequencies but massive parallel resources, so the best way to achieve high performance is to leverage this parallelism.

Finally, we leverage eBPF instruction-level parallelism, performing a static analysis of the programs at compile time, which allows us to execute several eBPF instructions in parallel.

Finally, the authors have this short note about being able to load programs on the FPGA at runtime:

In fact, hXDP provides dynamic runtime loading of XDP programs, whereas solutions like P4->NetFPGA [56] or FlowBlaze need to often load a new FPGA bitstream when changing application.

This note tells us something important about the design that is never explicitly said in the paper: hXDP doesn’t execute BPF programs like Netronome’s SmartNICs do, it interprets them. The FPGA runs a sort of eBPF interpreter. Loading a new BPF program doesn’t require changing the interpreter and therefore removes the need to load a new FPGA bitstream. The drawback of using an interpreter is that it will likely have lower performance than if BPF programs were compiled into an FPGA bitstream.

Unlike previous work targeting FPGA NICs [1, 45, 56], hXDP does not assume the FPGA to be dedicated to network processing tasks.

As said before, hXDP doesn’t consume all of the FPGA’s compute resources. That’s actually a nice goal. I find research designs for programmable devices, in particular P4 devices, tend to use a lot of resources, leaving little space for other applications on the device. In practice, if you’re designing a new P4 load balancer for a SmartNIC, it is unlikely to be the only piece of software running on the NIC. And even if it is the only piece of software on the NIC, the production-ready version of that load balancer will likely be a bit more complex than your research prototype. So, in any case, you want to keep some free space to make the design viable.

That being said, if I’m ready to use all of my FPGA’s resources, can I still get higher performance with hXDP?

Before diving into the design of hXDP, the authors describe a simple stateful firewall, to be used as a running example in the design and as a target for evaluations.

The simple firewall first performs a parsing of the Ethernet, IP and Transport protocol headers to extract the flow’s 5-tuple (IP addresses, port numbers, protocol). Then, depending on the input port of the packet (i.e., external or internal) it either looks up an entry in a hashmap, or creates it. The hashmap key is created using an absolute ordering of the 5 tuple values, so that the two directions of the flow will map to the same hash. Finally, the function forwards the packet if the input port is internal or if the hashmap lookup retrieved an entry, otherwise the packet is dropped. A C program describing this simple firewall function is compiled to 71 eBPF instructions.

The firewall is a simple connection tracking program, good as a running example, but probably not very telling for evaluations. It is lacking any enforcement of access control lists (ACLs) and it looks like it only supports one direction—supporting both directions would require a second lookup with the reverse 5-tuple. Finally, unless the authors left out those details, it doesn’t track sequence numbers and, when connections are blocked, packets are just dropped.

The authors use this simple program to highlight the challenge faced when building hXDP. Even though the program is very simple (71 instructions), simply running with an eBPF interpreter on the FPGA would result in only ~38% of the throughput achieved with a single 3.7GHz CPU core running the same program. Not good enough.

To achieve higher throughput numbers, the eBPF bytecode has to be tailored to the FPGA context.

Compile-Time Optimizations

Specializing the bytecode for the FPGA happens through a series of steps:

- The control flow graph (CFG) of the BPF program is built.

- Bytecode-to-bytecode transformations are applied on each code block.

- Bytecode instructions are assigned to lanes to parallelize their execution on the FPGA.

Bytecode-to-bytecode transformations must happen after the CFG is parsed to know where jumps happen and avoid grouping instructions together if a control flow can jump in between them. Applying such transformations on the CFG’s code blocks avoids that because all instructions in a code block are by definition guaranteed to be executed if any one of them is executed, that is, all jumps to a code block are jumps to the first instruction of the code block.

When targeting a dedicated eBPF executor implemented on FPGA, most such instructions could be safely removed, or they can be replaced by cheaper embedded hardware checks. Two relevant examples are instructions for memory boundary checks and memory zero-ing.

hXDP includes several types of bytecode-to-bytecode transformations:

- Some instructions, cited above, can be removed on FPGA. Those include instructions to initialize variables and bounds checks.

- Some instructions can be grouped into a single, FPGA-tailored instruction as shown below with the 3-operands instructions and the parametrized exit.

Finally, hXDP parallelizes the execution of eBPF instructions through a compile-time analysis. The authors describe the algorithm to assign instructions to parallel execution lanes as follows. The algorithm works at the level of the code blocks that make the program.

For each block, the compiler assigns the instructions to the current schedule’s row, starting from the first instruction in the block and then searching for any other enabled instruction. An instruction is enabled for a given row when its data dependencies are met, and when the potential hardware constraints are respected. E.g., an instruction that calls a helper function is not enabled for a row that contains another such instruction. If the compiler cannot find any enabled instruction for the current row, it creates a new row. The algorithm continues until all the block’s instructions are assigned to a row.

The algorithm has other optimizations to parallelize instructions belonging to different code blocks. It looks like a heuristic but that isn’t explicitly said.

Hardware Design

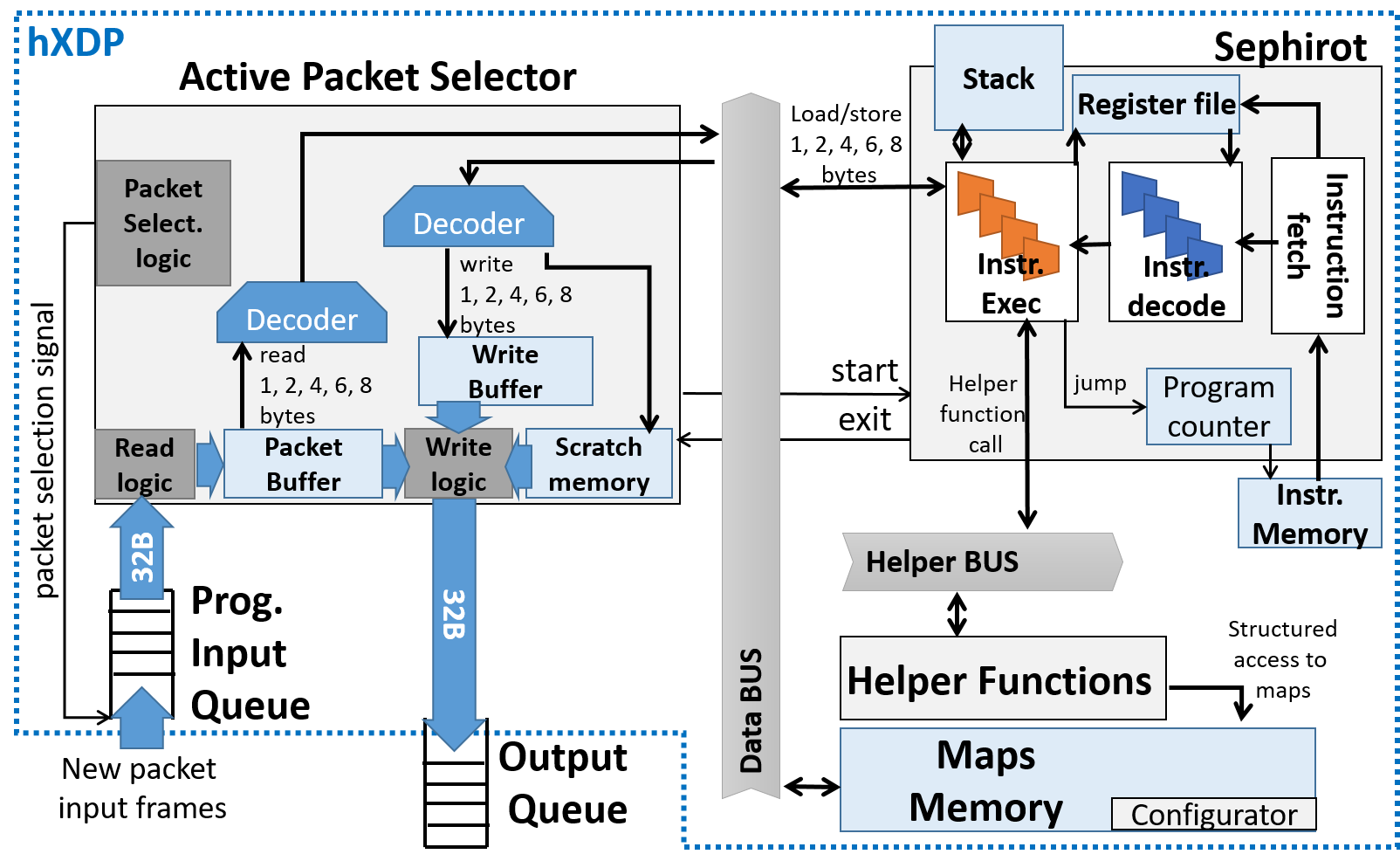

The hardware design includes not only the eBPF interpreter, but also the helper implementations and the infrastructure needed for maps. This is similar to the existing Netronome SmartNIC and is necessary to reduce the number of transactions on the PCIe bus.

Our IP core comprises the elements to execute all the XDP functional blocks on the NIC, including helper functions and maps.

At the hardware level, when new packet frames arrive, the following steps are taken:

- The Active Packet Selector component receives and decodes packets.

- That first component pings Sephirot to start the execution of the BPF program.

- Sephirot fetches, decodes, and executes bytecode instructions.

- If a packet load/store is required, Sephirot requires or sends that data over the data bus. If a helper call is decoded, the helper function module is called over the helper bus.

- When an exit instruction is decoded, Sephirot pings the Active Packet Selector to write data to the packet and send it out.

As an optimization, hXDP is able to start executing the BPF program as soon as the first frame is received, without waiting for the full packet.

Here, it is worth noticing that there is a single helper functions submodule, and as such only one instruction per cycle can invoke a helper function.

That seems reasonable. You usually have tens of bytecode instructions for every helper call.

Helpers are a big part of the BPF subsystem. Yet the paper has very few details about their implementation. In the latest Linux versions, 40 different helpers are supported for XDP programs, including tail calls, FIB lookups, spin locks, etc. It’s unclear whether hXDP can and does support any of these.

Evaluations

I had several questions before reading the evaluations:

- What throughput do they achieve with these compile-time optimizations + runtime interpreter?

- Can the tradeoff between performance and FPGA resource usage be controlled? Can they simply grow to use more lanes?

- How effective are the compiler optimizations? How effective is the assignment of instructions to lanes?

- How much space are they using on the FPGA?

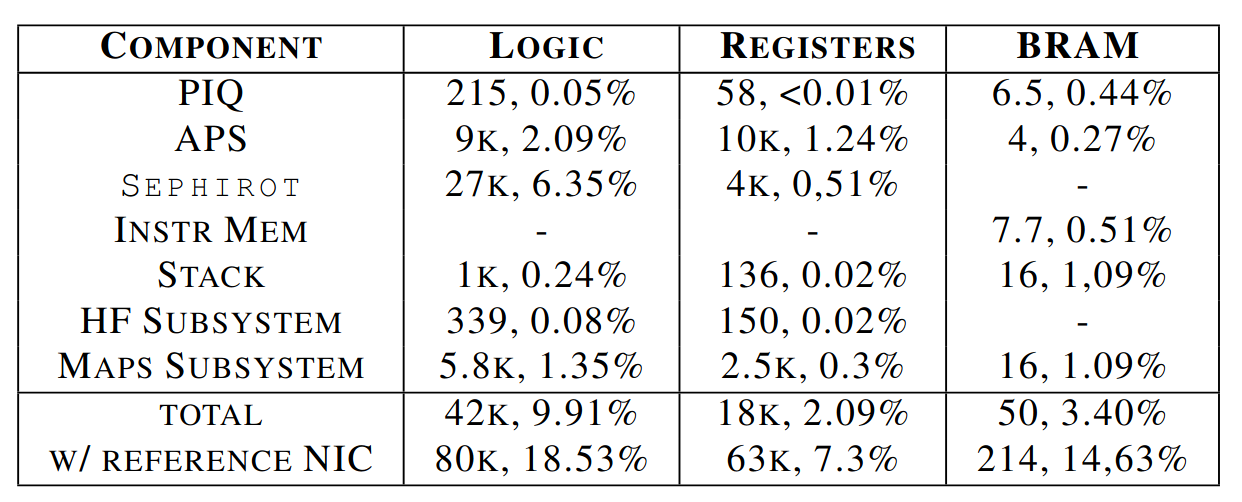

The evaluations open with the answer to that last question.

We have to look at the total with reference NIC for a fully-functional NIC. As expected, the resource usage is very reasonable and, in particular, hXDP consumes little resources on top of the reference NIC. It is also expected that the eBPF interpreter, Sephirot, is the main consumer of logic resources.

The authors then report the relative reduction of the number of bytecode instructions for each of the five compile-time optimizations: removal of variable zeroing, removal of bounds checks, use of new 3-operands instructions, use of parametrized exit instructions, and use of 6B load/store instructions. For Katran, the parametrized exit instructions are the least effective with only ~4% reduction, whereas the 3-operands and the removal of bounds checks are the most effective with ~10.5% and ~11% reductions.

The low effectiveness of the parametrized exit instructions is expected: there are usually few exit instructions per program, so the potential gain is lower. The ~10.5% reduction from removing bounds checks however came as a nice surprise to me. I would also expect BPF programs to have few bounds checks; they are required during packet parsing but rarely after.

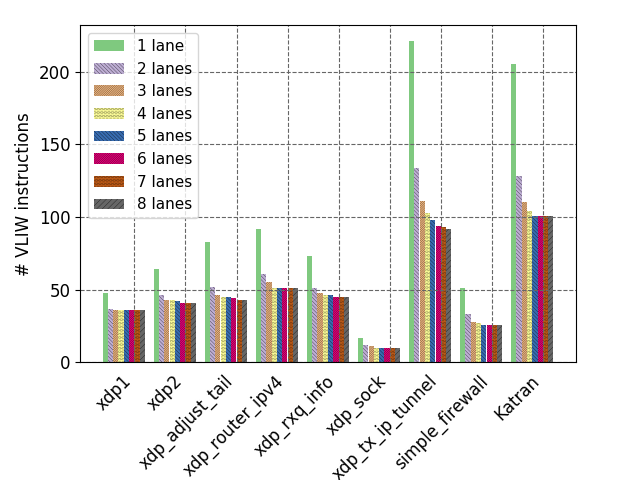

The evaluations also answer my questions on whether growing the number of lanes can improve performance. They count the number of Very Long Instruction Words (VLIW) as they increase the number of lanes. With 8 lanes, each VLIW can contain a maximum of 8 bytecode instructions. The actual number of bytecode instructions contained in each VLIW, and therefore the number of VLIW needed, will depend on the effectiveness of the parallelization.

The plot clearly shows that, regardless of the program being tested, the performance plateaus after four lanes. As far as I can see, the algorithm to assign bytecode instructions to lanes is a heuristic, but it’s unclear how much margin for improvement it has.

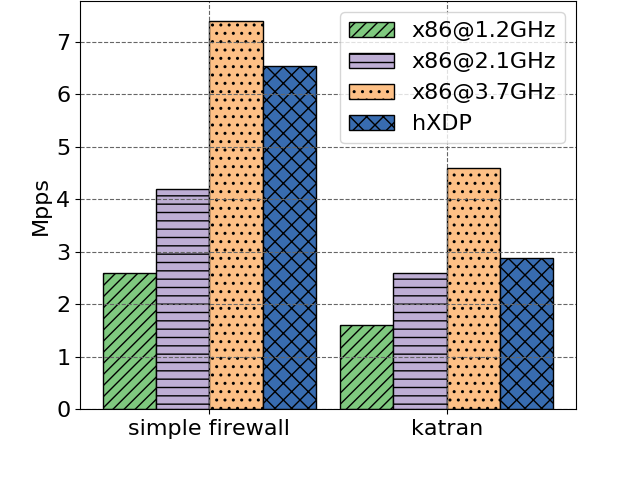

Let’s now have a look at the throughput numbers. The authors compare hXDP to an Intel Xeon E5-1630 v3 core running at different frequencies, for both Katran and their stateful firewall.

To me, this is the most disappointing part of the evaluation: even with the low resource usage I would have expected the FPGA to outperform a single CPU core. With the Katran program, hXDP barely outperforms the CPU core when running at 2.1GHz. To be fair, 2.1GHz CPUs are probably more common in data centers than 3.7GHz’s. Nevertheless, if you can easily scale your application running on a CPU by using more cores, it’s unclear if the same is true for the FPGA.

In those same throughput measurements, there’s a weird note on some of the results for the Linux XDP examples.

Second, programs that always drop packets are usually faster on x86, unless the processor has a low frequency, such as 1.2GHz. Here, it should be noted that such programs are rather uncommon, e.g., programs used to gather network traffic statistics receiving packets from a network tap.

And another a bit later that seems to contradict the first…

hXDP can drop 52Mpps vs the 38Mpps of the x86 CPU core@3.7GHz, and 32Mpps of the Netronome NFP4000.

I would expect BPF programs that drop packets to be a lot faster on the NIC because dropping at the NIC avoids PCIe transactions. And such programs are certainly not uncommon; DDoS mitigation was one of the first motivations to have XDP in Linux. I am probably missing something here. Or maybe some of the Linux examples are slower not because they drop packets but because they update drop statistics…?

I would strongly encourage you to read the paper for its additional performance results. There are a lot of results I didn’t comment here, including microbenchmark comparisons to Netronome’s SmartNIC, latency numbers, and an impressive comparison of hXDP’s static instructions-per-cycle (IPC) to the runtime IPC of the x86 core.

Future Work

The future works section has two encouraging notes I wanted to highlight. First, the authors were able to optimize the simple firewall further, so there is clearly margin for improvement in the compile-time optimizations.

For instance, we were able to hand-optimize the simple firewall instructions and run it at 7.1Mpps on hXDP.

Second, with a new memory access system, it should be possible to run hXDP with several Sephirot instances.

hXDP can be extended to support two or more Sephirot cores. This would effectively trade off more FPGA resources for higher forwarding performance. For instance, we were able to test an implementation with two cores, and two lanes each, with little effort. This was the case since the two cores shared a common memory area and therefore there were no significant data consistency issues to handle. Extending to more cores (lanes) would instead require the design of a more complex memory access system.

That would make it possible to easily trade FPGA resources for higher performance results.

Conclusion

All in all, this is a well-written paper on what seems to be a good idea. The design is nice and moves a lot of the complexity to the compiler. Definitely worth a read!

With that, I’m going to go check out the code to try and figure out the technical details that are missing from the paper. I will leave the final note to the authors:

In fact, we consider hXDP a starting point and a tool to design future interfaces between operating systems/applications and network interface cards/accelerators. To foster work in this direction, we make our implementations available to the research community.

Thanks Quentin and Yoann for the reviews!