Complexity of the BPF Verifier

A while ago I gave a talk on the BPF verifier at our internal system security seminar. As an introduction, I showed a simple, annotated plot of the evolution of its number of lines of code over time. The verifier ensures BPF programs are safe for the Linux kernel to execute. It is therefore critical to Linux’s robustness and security1. In this post, I’ll explore the verifier’s size and complexity over time through a few additional plots.

Update for the 5.5 Release

Linux v5.5 comes with type checking for BPF tracing programs, made possible by BTF.

Thus, BTF, and its main source file at kernel/bpf/btf.c, now play a role in the verification of BPF programs.

I’ve updated the statistics retroactively, from Linux 4.18, when BTF was introduced, to take this into account.

Verifier Size

Let’s start with the simplest metric of complexity and plot the evolution of the number of lines of code (LoC).

The verifier lives at kernel/bpf/verifier.c2, but since Linux v5.5, it relies on BTF at kernel/bpf/btf.c for type checking.

For the first plot, we can compute the number of LoCs with:

sed '/^\s*$/d' kernel/bpf/{verifier,btf}.c | wc -l

To compute the same without comment lines, I used Lizard.

The plot starts at v3.18, when the current ahead-of-time verifier for eBPF was added. Before that, verification was done at runtime.

The annotations on the plot show the new features that contributed the most to each LoC increase: direct packet accesses, function calls (bpf-2-bpf), reference tracking… The logs can be easily explored with the following command:

git log --pretty=oneline --stat v5.4..v5.5 kernel/bpf/{verifier,btf}.c

Now, there’s clearly a sharp increase of the number of lines over the last few releases.

But that’s only fair given that several new features have been merged in the BPF subsystem recently (e.g., bpf_spin_lock, bounded loops, and type checking).

Using the following command, let’s instead compare the size of the verifier with that of the whole BPF subsystem3:

sed '/^\s*$/d' kernel/bpf/*.c kernel/trace/bpf_trace.c \

net/bpf/*.c net/sched/*_bpf.c net/core/filter.c | wc -l

The verifier initially made up 40% of the BPF subsystem, but that number kept decreasing toward 20%… until the addition of BTF in v4.18.

Since then the size of the verifier+BTF has been growing faster than the rest of the BPF subsystem.

It takes a lot of code to resolve and check BPF types loaded with the BPF programs and the verifier increasingly relies on BTF to enable new features (e.g., bpf_spin_lock and type checking).

Cyclomatic Complexity

The number of lines of code is often a poor metric of a code’s complexity though. After all, a lot of the verifier’s line of codes are simple switch statements over helpers and program, map, and register types. Let’s complete our analysis with another metric, McCabe’s cyclomatic complexity.

In his 1976 paper, McCabe defines the cyclomatic complexity of a function as the number of linearly independent paths in the code, those paths from which all others can be generated by linear combinations.

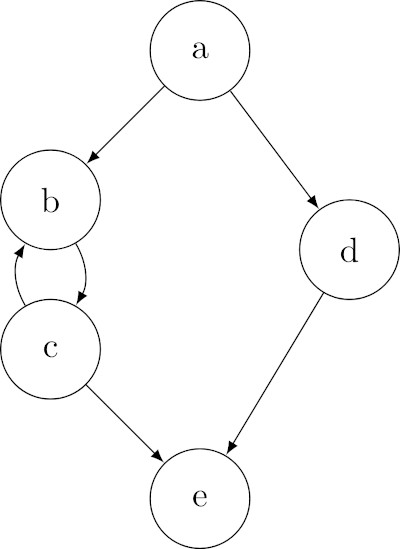

For instance, the following function has ade, a(bc)2e, and abce as linearly independent paths.

Path a(bc)3e can be constructed from 2 * a(bc)2e - abce.

Given a function, McCabe shows that the cyclomatic complexity can be computed as either one of4:

cyclo. complex. = vertices - edges + 2

= code blocks - transitions between code blocks + 2

cyclo. complex. = predicates + 1

Which gives us a cyclomatic complexity of 3 for the above function. See the paper for other examples.

But how do we interpret this metric? Well, McCabe’s idea is that the control flow of a program tells us more about its complexity than the number of lines. Unfortunately, the number of paths may well grow exponentially with the control flow complexity5. In contrast, by ignoring combinations of already counted paths, the cyclomatic complexity is commensurate with the control flow complexity.

To compute the cyclomatic complexities of the BPF verifier, I used Lizard again.

Lizard gives us the cylomatic complexity for each function in verifier.c and on average, over all functions.

I used the -m option to count entire switch statements as a single if, instead of counting each case6:

python lizard.py -m kernel/bpf/{verifier,btf}.c

As we can see with the blue marks, the cyclomatic complexity is quite stable, with even a slight decrease over the last few releases. This decrease is actually caused by an increase of the number of small, uncomplex functions. This small functions are numerous in the BTF code in particular, as can be seen by the drop for Linux v4.18. The verifier grew from 32 to 414 functions, most of which are very simple.

The 10 most complex functions, on the other hand, are getting more complex. In the v6.12 release, these functions are:

167 do_misc_fixups

112 check_kfunc_call

110 check_kfunc_args

103 do_check

93 check_helper_call

93 check_mem_access

88 check_map_func_compatibility

82 check_alu_op

72 bpf_check_attach_target

69 check_cond_jmp_op

Any Other Complexity Metrics?

Given the two metrics I considered, it seems clear that the BPF verifier is getting more complex. Whether this is an issue is a matter of opinion though. But at least now we have metrics on which to base that opinion. By the way, any ideas of other metrics I should include?

In addition, the two above metrics have their own limit: all lines of code (resp. independent paths) don’t have the same complexity.

Besides, the verifier.c file does not only contain code for the verification of BPF programs.

It also performs some amount of rewriting for BPF calls, the map references, and BTF.

It looks debatable to me that these should be included in any complexity measure7.

In the end, even with a perfect measure of complexity, it wouldn’t tell us if this is a problem. One thing is clear: we need to keep reviewing and testing the verifier to avoid bad surprises.

Thanks to Céline, Quentin, and Aurélien for their reviews of this first post!

-

Currently, Linux allows only two BPF program types to be loaded without root privileges. ↩

-

Since v4.9, some internal structures are also exposed at

include/linux/bpf_verifier.h. ↩ -

Not including JIT compilers, samples, tests, and tooling. ↩

-

He also proposes a quick visual method to devise the cyclomatic complexity for planar graphs. ↩

-

for (i = 0; i < 100; i++) { x = input(); if (x) acc += x; } return acc;↩ -

As seen above, the verifier has many of these switch statements, which by themselves do not make the code more complex. The results are similar when counting all

cases, with higher numbers but the same functions in the top 10. ↩ -

Part of the bytecode rewriting happens for security reasons. For example, divisions are patched to skip divisions by zero. When inlining helper calls, some runtime checks are also added. It might therefore be difficult to completely separate rewriting and verification. ↩